Investing Psychology

Fear Is Profitable

- Volatility is a revenue engine

- Your instincts are treated as inputs

- The cost of reacting is invisible but compounding

Most people think fear is an emotional flaw in investing. But let's consider it as a pillar of how the industry makes money.

Fear creates movement. Movement creates transactions. And transactions create revenue, just not for the person who's scared.

That movement doesn't just happen in a vacuum. It feeds three major groups:

- Financial media

- Brokerages and trading platforms

- Active fund managers and advisors

But before going further, take second to look at these two tabletops below...

Most people say the one on the left is longer, and they're certainly different in size. But they're the same size in every dimension and if you're the kind of investor we described in the previous lesson, you're probably grabbing a ruler right now.

The issue isn't eyesight, it's perception.

Your brain fills in what it assumes is true based on angles, context, and past experience.

And that's exactly how fear enters investing. We don't respond to reality. We respond to whatever our perception tells us is "true" in the moment. That gap between what is and what feels real is worth billions to the people who know how to trigger it.

Here's What That Looked Like During the COVID Crash

- Market volatility jumped 400%

- CNBC viewership increased more than 160%

- Bloomberg's web traffic doubled

- Google search interest in "stocks crash" spiked 2,300% in one week

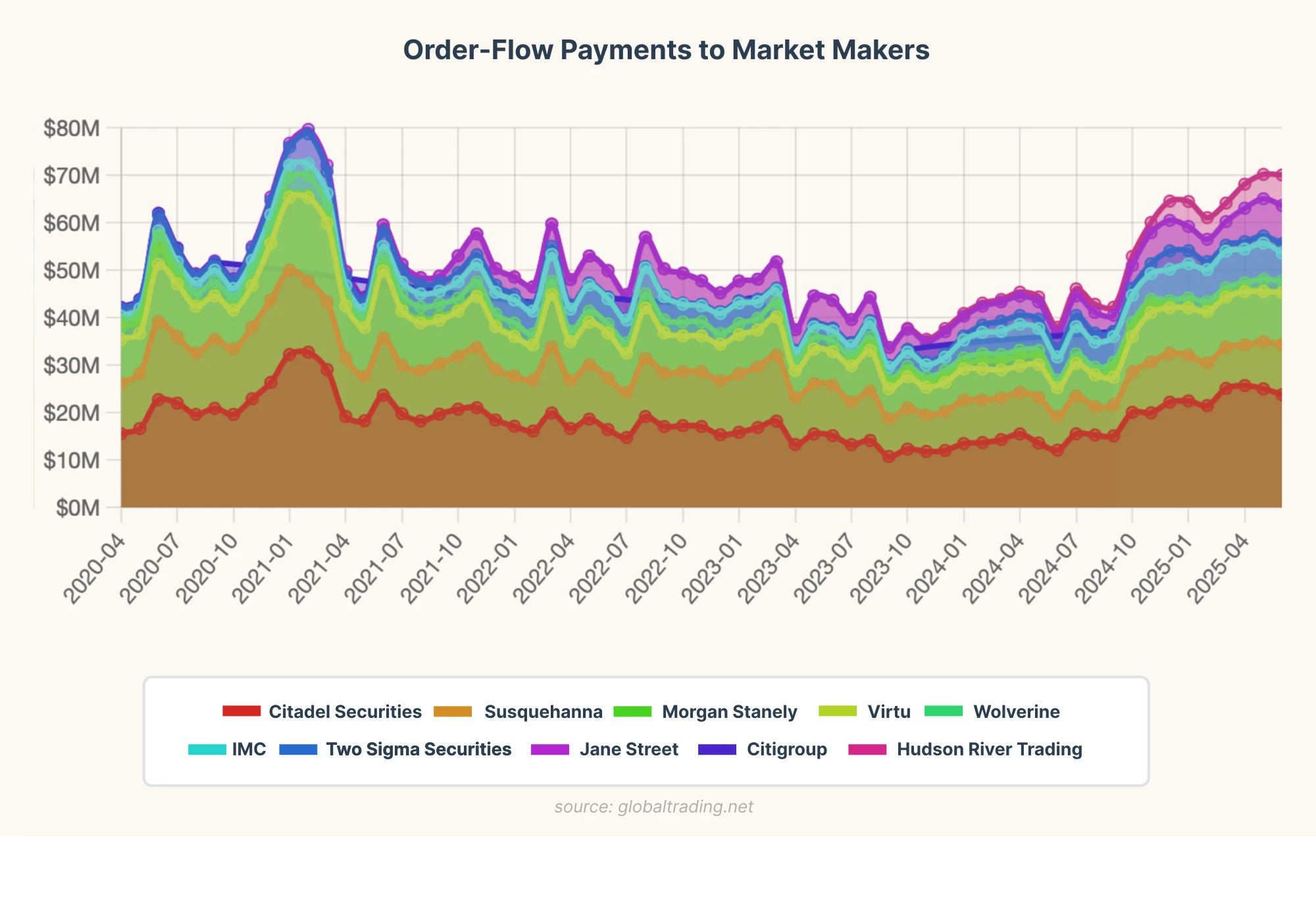

The same thing happens inside the trading platforms. When fear hits, trading volume climbs, and the profits flow to the people routing those trades. At the peak of the 2021 panic, retail investors made up nearly a quarter of all U.S. equity volume. Robinhood made more than 75% of its revenue from selling those orders to market makers, not from advice or returns. The chart that tracks order-flow payments tells the story directly.

Every spike in fear shows up as a spike in revenue for firms that never have to place a single trade themselves.

This pattern extends to active management. When markets are calm, people ignore complex products. When uncertainty rises, they start paying for action and risk reduction.

Actively managed funds take in more money during downturns than during bull markets, even though over any ten-year window, most still underperform the benchmarks they sell against.

And the most important part: the damage doesn't come from being wrong about the market, it comes from reacting at the wrong time. A calm investor places one trade. A fearful investor places five.

The research is consistent:

- High-trading retail investors underperform by 6–7% a year

- Men trade 45% more than women and earn lower returns

- The average investor captures only about 60% of the returns of the assets they hold, because they move in and out at the wrong moments.

What this lesson is waking you up to is simple: your reactions don't just impact your returns, they feed a machine that depends on you mistaking emotion for information.

You don't beat fear by feeling differently...

You beat it by removing the moments where fear gets to decide.

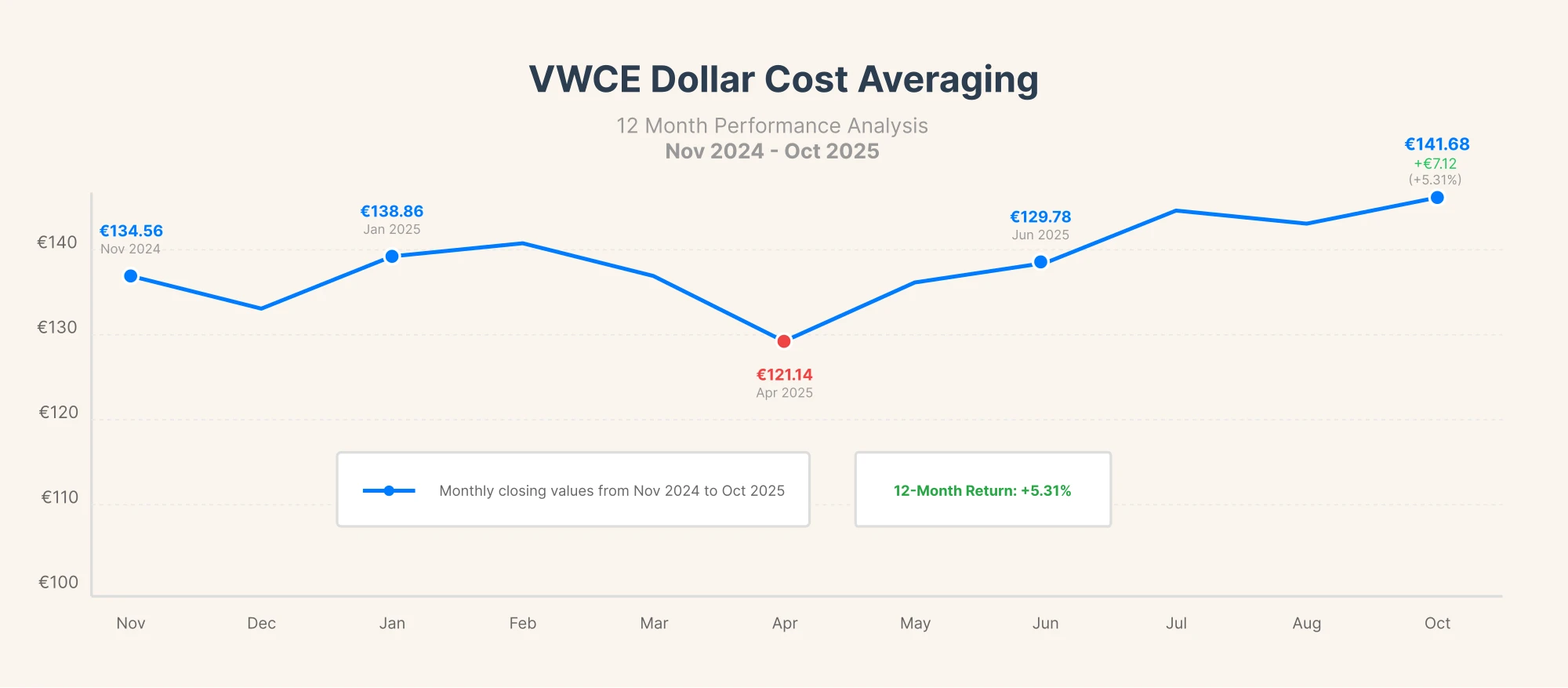

One of the simplest tools is dollar-cost averaging: a time tested strategy of investing the same amount on a set schedule, regardless of what's in the news. In other words, sticking to the plan you established in chapter one.

Here's a snippet of how it works.

Over just one year, you can already see the pattern: prices fall, recover, dip again, and climb.

Stretch that to a decade or thirty years and the same rhythm repeats, just with bigger swings.

But funds like VWCE don't rise by accident. Trough one action you are investing in hundreds of companies across the world: Apple, Toyota, Nestlé, Microsoft, Samsung, LVMH, etc.

When these businesses grow (which the only reason they exist) the fund captures that growth automatically.

It's a smart investment piggybacking on the expansion of the global economy.

And that's where dollar-cost averaging matters.

By investing the same amount through both the dips and the recoveries, the declines lower your average cost and the rebounds compound your gains.

We'll look at more examples of this later on.