Investing Psychology

Why High Performers Make Bad Investors

- The rules of success don’t apply here

- The less is more paradox

Luck and circumstance are real. Just ask Bill Gates he happened to attend one of the only high schools in the world with a computer, which gave him a head start most people couldn't dream of.

That said, we can all agree that effort is

If you study, you pass.

If you go the extra mile, you get promoted.

If you hit the bar on Tuesday night, you pay for it Wednesday morning.

That's cause and effect. A deterministic system where 2 + 2 equals 4.

But in markets effort rarely maps to outcomes.

Here, 2 + 2 might be 4. Or 1. Or 9. And you don't get to ask why.

That's one of the hardest mindset shifts for people who are used to winning through productivity, clarity, and control.

In markets, intelligence, work ethic, and effort can turn into liabilities. What wins instead is the kind of patience that looks like incompetence, simplicity that feels like laziness, and restraint that resembles cowardice, especially to the ambitious and the driven.

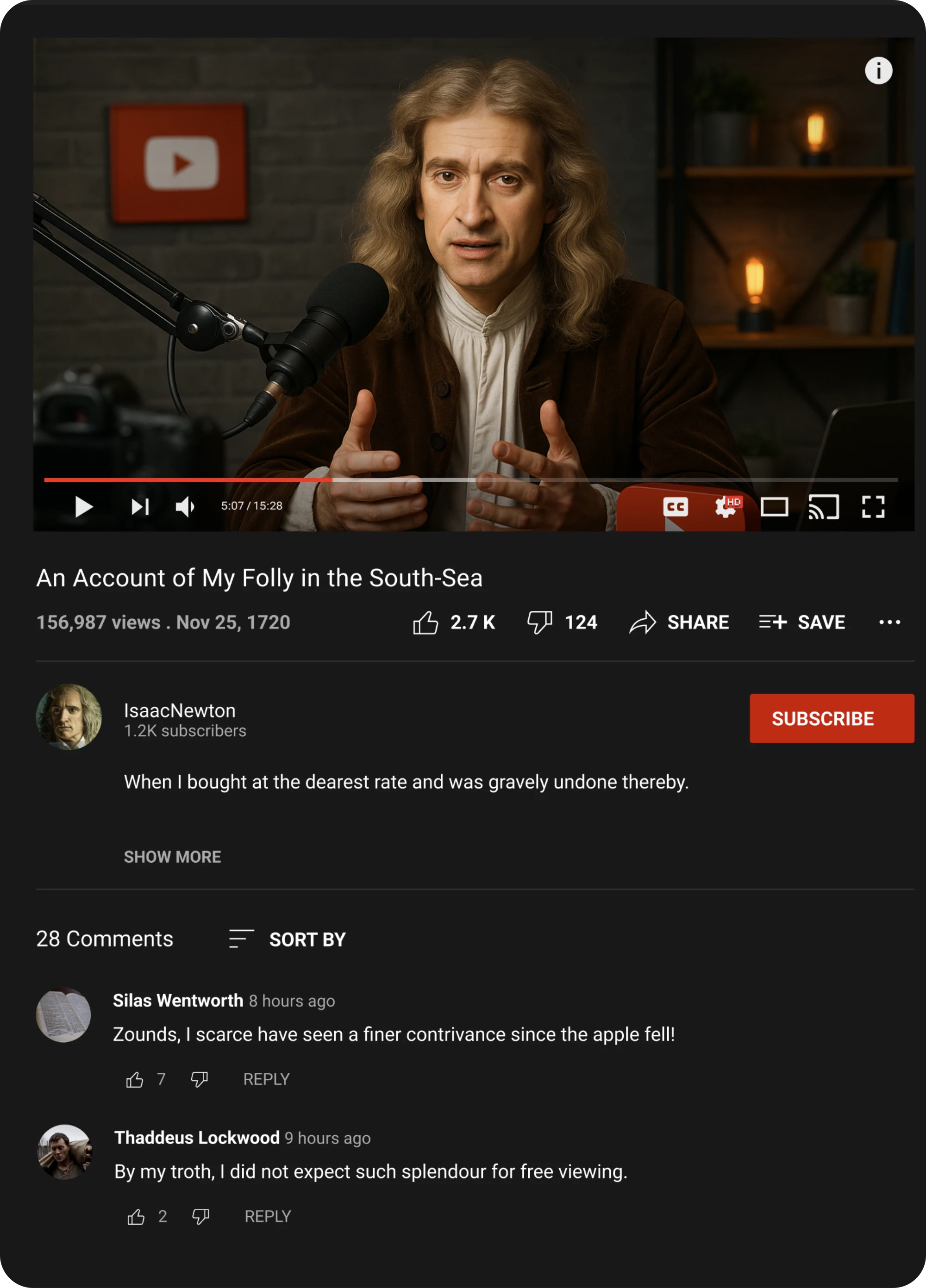

Isaac Newtons Investing Blunder

Everyone knows Isaac Newton as the father of gravity and modern physics. Almost no one remembers he was also an investor, who was taken apart by one of history's first major bubbles.

In 1720, Newton bought shares in the South Sea Company, which had been chartered to consolidate Britain's national debt.

He sold early for a roughly £7,000 profit, but the stock kept climbing. Friends and colleagues were getting richer, and Newton, confident in his analytical powers, reinvested about £20,000 near the peak, essentially his life savings.

When the bubble burst, he lost it all: about £20,000 at the time, equivalent to roughly £3-4 million today.

The mental traits that served him so well in science, intelligence, confidence, decisiveness, failed in a probabilistic, crowd-driven system.

After the crash, he famously said:

"I can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of men"

How the world lost today?

The Same Psychology Powers An Entire Business Model

What you saw in the previous lesson, a globally diversified, low-cost portfolio that earns 7–8% a year over time, is enough for most people to build real wealth. The data proves it. The history proves it. The math proves it.

But almost everything in the financial industry is built to pull you away from that simplicity, not because it doesn't work, but because it doesn't pay.

An in-depth study by S&P Dow Jones Indices found that over a ten-year period, 86% of active equity fund managers underperformed the benchmarks they're paid to beat.

Stretch that to fifteen years and the failure rate hits 90–95% in most regions.

These aren't amateurs. They have teams, models, credentials, yet the average investor would be better off in a basic low-cost index, like VT or VWC.

If the system rewarded skill, those numbers wouldn't exist. Active management survives because it monetizes the exact impulses that make smart people underperform: the urge to act, the need to be right, and the fear of doing nothing.

The incentives are simple:

- The more you trade, the more they earn.

- The more you chase performance, the more they can sell.

- The more complex it looks, the more they can charge.

Legendary investor Charlie Munger said, "Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome."

Jack Bogle's version is simpler: "In investing, you get what you don't pay for."